Julie Gould 00:09

Hello and welcome to Working Scientist, a Nature Careers podcast. I’m Julie Gould. This is the second episode of a series called The last few miles: planning for the late-stage career in science.

Retirement is a major life transition, one that many of us don’t ever really think about. Scientists and researchers are all very busy with all the other thousands of things going on in their lives. How could you possibly find time to think about retirement? But as we heard in episode one of this series, it comes to us faster than you might think.

So in this episode, we’re looking at, what is retirement?

Inger Mewburn 00:50

I still don’t know.

Julie Gould 00:52

This is Inger Mewburn from the Australian National University in Canberra. She’s a later stage career researcher who, at the moment, is planning on retiring in about 10 years.

Inger Mewburn 01:01

When I think about it in my mind, I think of my grandparents who were retired the whole time I knew them. And it seemed like they went to the shops a lot, you know, and ran errands and seemed to have this weird daily routine when they didn’t really.

It took me ages to realize they didn’t have a job, because I lived with them at this stage for quite a bit of my childhood. So I was up close and personal with retired people. So it never seemed like rest to me, they seemed quite busy.

And then I’ve then subsequently observed lots of people in my academic career retire and just still be at work every day. And then some people I know who’ve really taken retirement very seriously have sort of set other models for me, so I really don’t know what it is yet.

Julie Gould 01:44

What Inger saw her grandparents do is what Roger Baldwin, a retired professor of higher adult and lifelong wducation and the current chairperson of AROHE, The Association of Retirement Organizations in Higher Education, sees as an outdated definition of retirement.

Roger Baldwin 01:59

Retirement used to mean a period of well deserved leisure after the end of one’s career employment. If you Google the word retirement and click on images, you mostly see pictures of people sitting on the beach, playing golf or sailing on a sailboat. It’s this concept that retirement was a period exclusively of not working and of leisure.

Julie Gould 02:26

So I actually did this, I Googled retirement and looked at the images. And he was right. There are a lot of photos of white or gray-haired men and women in warm, sunny climes, sitting on deck chairs, drinking a cocktail, and smiling like they don’t have a care in the world.

Roger Baldwin 02:41

Retirement has a much more complex meaning in today’s world. In fact, I’m not really sure that retirement as a term is very meaningful anymore. But I’m not sure what the alternative is.

But basically, it’s an open ended period after the conclusion of one’s main professional employment, that has almost infinite potential opportunities.

So it can for some people continue to mean a period of leisure, or for other people, it can be an opportunity for continuing employment, perhaps on a part-time basis, or a volunteer basis, but a period of continuing engagement in a way that is fulfilling and enjoyable to the retiree.

Julie Gould 03:32

That could mean, as Roger said, taking your leisure time seriously and going somewhere to lie on a sun lounger and drink a cocktail. But for many academics, it means continuing with what you’ve been doing for the last 40 or 50 years of your life, something that has brought you joy and fulfillment and meaning.

Roger believes that it’s incredibly important to look at this particular stage of the career ladder.

Roger Baldwin 03:52

There’s so much evidence that if people can find purpose and meaning and opportunities to continue contributing, they’ll reap all kinds of benefits personally, but all kinds of benefits for the society as well.

Julie Gould 04:07

Another reason to look at scientists in later stages of their academic career, says Shirley Tilghman, the previous president and emeritus Professor at Princeton University in the USA, is because there are simply more people in this career stage now.

Shirley Tilghman 04:20

If you look at the demographics of the faculty across all institutions that I know of, certainly here in the United States where I’ve studied this, we are seeing the greying of the professoriate, the greying of the academic workforce. Individuals, you know, the mean age is getting older and older and older.

Julie Gould 04:42

One cause of this growing sector is that there have been hiring freezes across academia, bringing fewer younger people into the professorship positions. But another reason is …

Shirley Tilghman 04:51

… this reluctance to think about retirement. Now, you know, I grew up in an age when many companies had retirement ages of 60 and 65. Now, that just seems implausible today. And, and it’s implausible in part because we are living well longer. And so retirement ages around 60 or 65, just don’t make sense.

Julie Gould 05:18

Shirley formally retired from Princeton University in 2021.

Shirley Tilghman 05:23

I formally retired and I love to tell all of my colleagues that I’m retired, because it’s almost a word that people are afraid of. And so, demonstrating that, that one can live a healthy and happy and fulfilled life, retired from your, the job that you last had, I think, is a message I’m trying to deliver all the time.

Julie Gould 05:48

And so what does this happy, fulfilled, retired life look like for you? Because I know that you’re still active in publishing and getting involved in committees and, and all sorts of things.

Shirley Tilghman 06:00

Yes, and I think I do need to be very clear that my retirement meant formal retirement from Princeton University where I’d been employed since 1986.

It did not mean that I ended the kind of work that I had been doing since I stepped down from the presidency, which is to serve on a couple of university boards, college boards, because I can take advantage of all of the knowledge that I gained while I was a president at Princeton.

And what has actually been great pleasure for me is to continue doing some science policy advising, particularly around the area of philanthropy. So, I’ve had a busy and rich time, despite the fact that you know, I declare that I’m emerita and retired. But I continue to do lots of other things.

Julie Gould 07:01

There are different ways for academics to retire. One way, as Roger inclined, is to leave academia behind and never look back. But to be honest, those kinds of retirees from academia are few and far between. Many stay involved in one way or another.

Some take on the role as an emeritus professor, like Shirley Tilghman. This is an honorary title that allows you to continue being involved with the university. Roberto Kolter became a professor emeritus at Harvard Medical School after retiring in 2018. For him, being an emeritus professor allows him to stay in contact with the university and his colleagues.

Roberto Kolter 07:36

Basically, all of the benefits that I had in terms of access to resources at Harvard, the ability to join all of the meetings, seminars, etc. That remains the same.

In fact, they even were giving me an office but I never used the office, because I was a lot remote and I’m also doing a lot of work on the main campus, not at the medical school. So, but the important thing really, as a message to people who transition to emeritus is that there are many ways to transition to emeritus.

In my case, I signed off that I will no longer be getting grants. Of course, I no longer get the salary. But other than that, I’m not running a laboratory, my interactions with my peers could remain the same.

Julie Gould 08:20

Carlos García Canal, an 80-year-old emeritus professor of physics at the University of La Plata, in Argentina, also took this title so that he could continue teaching at the university,

Carlos García Canal 08:31

The emeritus professor appointment is for the honour, only honorific title. But at the university, you have the right to lecture and for this lecturing you are paid with an amount. They’re very small, but it is enough for the medical problems, to pay the medical assistants.

Julie Gould 09:00

When Carlos first retired 15 years ago, it was a big shift for him and ultimately, one he didn’t like.

Carlos García Canal 09:06

I think that the moment of the retirement I feel some kind of depression because I feel that perhaps is the end of my activities. But it wasn’t that.

I start convincing the group of research that was under my direction, that I can be still useful for the research. And well, I was accepted. They decided that I can be a kind of person for consultations in science, and not only in my own group, but in all the department.

Julie Gould 09:49

He told me that he was required to officially retire from being a working academic when he turned 65. At this stage, Carlos handed over a project that he was the director of. Yet now that he’s 80 years old, he is still involved with this group and its research.

Carlos García Canal 10:05

I’m working, still hard on research, and I’m lecturing, for example, tomorrow I have lecture of electromagnetism at the university. So I’m very happy to be in a mental situation that allows me to continue with my career of a professor of scientists in my university. I feel that I’m still with some success in these activities.

Julie Gould 10:37

Carlos’ working weeks aren’t 40, 50, 60 hours long anymore. And since the pandemic, a lot of his teaching has gone online,

Carlos García Canal 10:45

So I go to the university, three times per week, during the morning, and during the afternoon I work at home, connected with a computer, with my students, with my colleagues, etc. And if I tire, I take a rest.

Julie Gould 11:06

Another position to take on is adjunct. Juergen Reichardt is an adjunct professor at the Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine at James Cook University in Australia. As part of his role, he is still required to be active and is regularly evaluated. His next renewal, in fact, is in the middle of 2025.

Juergen Reichardt 11:25

You really need to publish, you really need to be in grants, on grants. So it’s not that different from being active, it’s just that you don’t get paid any anymore. But you’re very much evaluated, especially when, when it comes up for renewal, whether you’re actually doing stuff, or whether you’re just sitting on your bum, and twiddling your thumbs.

Julie Gould 11:48

Juergen hopes to continue working in this way as long as he can.

Juergen Reichardt 11:51

As a proviso, as long as my mind works I’m happy to continue this as a lifelong activity. It’s clear that inevitably I will slow down.

So, I do keep quite active and maybe having that pressure that I need to renew it, that I need to demonstrate what I have done, that subtle pressure, because if I lose the office or the title, yeah, I won’t be happy about it, but it’s, you know, I don’t get paid. So the consequences aren’t as big.

But, so maybe that subtle pressure also helps me a little bit that I keep my CV up, that I keep doing things. They’re things that I enjoy, and so I continue to have results in terms of publications and grants.

So for me, that’s the way it works. And for as long as I can do it, I do want to continue to do it, ideally lifelong, although I fully understand at some point it will be at a slower pace than it’s now.

Julie Gould 12:51

For some, like Carlos Garcia Canal, retirement was forced on them by a mandatory retirement age. Others, however, are forced into retirement due to factors outside of their control. Graham Crow, an emeritus professor of social sciences from the University of Edinburgh, in the UK, has been retired for a few years now. And it was a trip to the accident and emergency room with a diagnosis of late onset asthma during his late 50s, as well as poorly parents and a long distance working commute from Southampton to Edinburgh, that brought his retirement into perspective.

Graham Crow 13:21

Health and family relationships and family responsibilities, and indeed partners retiring, those sorts of things, they all start to sort of factor in, in a way that I think, you know, when I was 45, I wasn’t thinking about those things.

But by the time I was in my late 50s they were sort of coming to the fore. Partly because other people were going through, or had recently gone through the same things. You go to lots of retirement dos and it gives you reason to think.

When you’re, when you’re 25, 35, you think you’re going to go on forever. By the time you get to your late 50s, I think that you know that, that shifts.

Julie Gould 13:59

And for others again, retirement is a choice.

Pat Thompson is a part-time professor of education at the University of Nottingham in the UK, although she lives in Australia. Her research focus is on academic writing and doctoral research. And this is actually a second career for Pat, who spent the first two decades of her working life as a teacher.

Since then, Pat has been working in academia for the last three decades, and is now working on, and planning her retirement. For Pat retirement means …

Pat Thompson 14:27

… having more control over what it is I want to do and doing less of some of the things I’ve been doing up till now. And that might sound a little bit vague, but I think there’s probably some parts of academic work that I want to continue, certainly for a while longer, but there are a number of things about, yeah academic work that I can quite happily leave behind me.

Julie Gould 15:02

Pat is working part time and plans to formally retire from the University of Nottingham when her latest project comes to an end towards the latter half of 2025. Until then …

Pat Thompson 15:12

… you know, one of the reasons I’m still doing things is because we’re in the second year of a three-year funded research program that, you know, I’m still involved in.

So, at the moment I’m still supervising a few doctoral researchers and working on this research project and trying to wrap up, and do the writing from, a big funded program, a big funded research program, looking at the arts in primary schools. So I’ve just got a whole lot of things to finish off before I can just solely go and melt metal.

Julie Gould 15:47

Here, Pat is referring to her retirement plan of making silver jewelry, something that she has been learning to do for a couple of years now. And Pat told me that even though she is planning for her retirement, she still argues with herself about whether or not to continue working,

Pat Thompson 16:01

I guess it’s because I kind of feel like on the one hand, you know, I should be done by now, I should be putting the feet up, you know, there’s this kind of unwritten expectation that, you know, you want to stop working and you want to spend, you know, the last bit of your life doing something else. Travelling or whatever.

And, yeah, yeah, I’d say there was, I’ve always just been, I guess, wrestling with this notion that, you know, I really should stop doing this. And the competing notion that no, actually, I’m really enjoying what I’m doing and as long as I appear to be productive and doing something interesting, you know, I, it’s okay to keep going.

Julie Gould 16:51

As an older academic, I wondered if Pat ever felt pressure from her institution to step back and retire. She told me that she didn’t. And this was because she’s still actively contributing to research and bringing in money.

Pat Thompson 17:03

I’m pretty productive, I publish quite a lot. So the kind of base level assessment of what I provide for the university is probably still considered to be, you know, kind of reasonable.

So in the UK, where a professor would be expected to be contributing a certain amount of papers and books that would be rated as what – well, you know, it’s a four star in the, in the UK context – would be rated at that level as your contribution to the institution. And I take that pretty seriously and I do feel that as an obligation. And so I think I do do that. And I think, you know, until, well, this this last round, I’ve also always brought in a fair bit of money, as well.

So I think in terms of, you know, the kind of key indicators that the institution might use, and I’ve had a lot of doctoral research and I’ve supervised a lot of doctoral researchers as well, so I think I have been pretty productive. And I think I’ve also pretty clearly signaled that I’m, that I’m winding down now. And so I don’t think I’m going to have any pressure to retire if I stick to the timeline that I’ve set.

Julie Gould 18:31

As with Carlos Garcia Canal, Pat Thompson hopes to find balance between purposeful active engagement and commitments to academia, and the freedom and flexibility to choose activities, leisure or otherwise, as they come along during her retirement.

Others find this more difficult, including Roger Baldwin.

Roger Baldwin 18:48

In retirement, one of the one of the benefits of it is the freedom and flexibility and you want to be able to take advantage of that. And I haven’t succeeded, developed the comfortable balance between engagement and having the flexibility to take advantage of opportunities when they come along.

Like if a friend calls and said, “Hey, there’s a really cool river cruise in Europe and I need somebody to go with me, would you be interested?” Right now it would be a challenge, (unless it was like six, six months or a year ahead), it would be a challenge for me to do that.

Julie Gould 19:26

The old work-life balance issue, that is an issue for young people, remains an issue for retirees as well.

Roger Baldwin 19:34

It has a different character to it, but it’s still that work-life balance issue, that’s absolutely right.

Julie Gould 19:42

In the next episode of The last few miles, we’ll look into another factor that impacts how people approach retirement. And that is this overwhelming feeling of potentially losing your identity when you step away from working as a researcher.

Thanks for listening. I’m Julie Gould.

You Might Also Like

Five ways increased militarization could change scientific careers

Ukrainian soldiers test drones in Donetsk, Febuary 2025.Credit: Serhii Mykhalchuk/Global Images Ukraine via GettyMilitary budgets are growing, especially in larger...

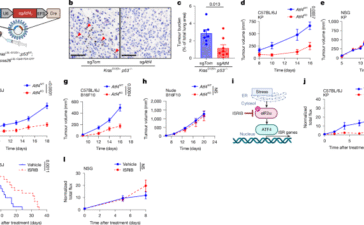

The integrated stress response promotes immune evasion through lipocalin 2

Cell linesThe KP cells used here were established previously66. Atf4 and Lcn2 knockout cell lines were generated by transient transfection...

How AI slop is causing a crisis in computer science

AI slop is flooding computer science journals and conferences.Credit: Quality Stock/AlamyFifty-four seconds. That’s how long it took Raphael Wimmer to...

The ‘astounding’ rise of semaglutide — and what’s next for weight-loss drugs

First established as a treatment for diabetes, semaglutide’s popularity as a weight-loss drug has opened the door to new therapies.Credit:...