(RNS) — When Jimmy Carter ran for president, his campaign advisers worried his Christian faith would be a political liability.

On a draft copy of the speech announcing his presidential candidacy, they urged him to soften his claim to being a Christian to avoid offending those who did not identify with his brand of religion. By leading with a reference to his religion, Carter was coming across “a little too much as ‘Old South,’” one adviser told him.

Carter insisted on keeping the phrase. Later in the campaign he even used the potentially more polarizing phrase “born again” to describe his Christian experience.

To the relief of Carter’s campaign strategists who worried that a Southern Baptist Sunday school teacher and church deacon might need to tone down his religiosity to win the presidency, Carter’s refusal to go along with their admonitions worked.

In the 1976 election, he carried every Southern state except Virginia, winning the votes of both Black Protestants and white evangelicals, as well as majorities among Catholics and Jews.

Four years later, a majority of white evangelicals turned against Carter, leaving historians and pundits to spend the next four decades asking what the born-again president had done to lose the votes of his fellow evangelicals.

Was Carter too evangelical for some of his campaign advisers but not evangelical enough for the Southern Baptists who started the Christian right?

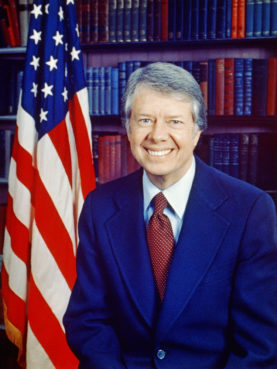

Portrait of President Jimmy Carter on Jan. 31, 1977. Photo by Karl Schumacher/LOC/Creative Commons

In reality, Carter was the wrong type of evangelical for the evangelicals of the Christian right — but an evangelical nevertheless, and one whose heartfelt faith pervaded his entire life.

In recent years, public opinion polls and scholarly studies of American religion have frequently divided white Protestants into two opposing camps: evangelical and mainline (or ecumenical) Protestants. But Carter defied that neat categorization by combining the fervor and religious experience of an evangelical with the social justice consciousness and acceptance of religious pluralism that characterizes many ecumenical Protestants.

Raised as a Southern Baptist in rural south Georgia, Carter (unlike some of his siblings) remained a faithful churchgoing Baptist throughout his life.

Yet he was never a fundamentalist. He embraced modern scientific accounts of the world’s origins and, after reading widely in 20th-century Christian theology, he came to accept critical biblical scholarship’s views of the Bible’s composition as well. Unlike the conservatives who wrested control of the Southern Baptist Convention in the 1980s, he was not a biblical inerrantist.

He did, however, describe himself as an evangelical — and not just because he was a Baptist, part of a tradition that had long emphasized personal conversion. He had firsthand experience of God’s presence and saving power, he said.

Although he had long been active in church, he believed he was “born again” in 1966, when he fully surrendered himself to God after losing the Georgia gubernatorial election to the segregationist Lester Maddox. Immediately after this religious experience, Carter took a mission trip to do door-to-door evangelism in Pennsylvania.

But at the same time that he worked with conservative Baptists to convert people to Christianity, Carter also became a supporter of civil rights for African Americans, a cause that many Southern Baptists — including most of the leaders of his home congregation in Plains — were not willing to embrace.

Former President Jimmy Carter and former first lady Rosalynn Carter answer questions during a news conference at a Habitat for Humanity project Oct. 7, 2019, in Nashville, Tennessee. Jimmy Carter wears a bandage after a fall the day before at his home in Plains, Georgia. (AP Photo/Mark Humphrey)

His views on race, politics and theology were shaped by his wide readings of Reinhold Niebuhr and other 20th-century theologians, but also by his encounters with social justice-minded Georgia Christians such as Koinonia Farm founder Clarence Jordan and Habitat for Humanity founder Millard Fuller. Carter learned from their examples that following Jesus led to interracial alliances and poverty relief, not conservative evangelical politics.

When Carter ran for president in 1976, he sounded to the press like a devout evangelical. He and his wife, Rosalynn, read the Bible together every night. He prayed constantly throughout the day. He asked his campaign staff to schedule time for him to attend church each Sunday. On trips to his home congregation, he frequently taught an adult Sunday school class, often in full view of the crowd of reporters who began attending.

But some conservative evangelicals questioned his piety. His willingness to drink alcoholic beverages in moderation raised eyebrows among a few teetotaling Baptists. His interview with Playboy magazine alienated many more.

In the end, Carter won the presidency in 1976 with the support of approximately half of the nation’s white evangelical voters and a majority of Southern Baptists.

The evangelicals who voted for Carter in 1976 were not motivated by Carter’s position on the issues, but his personal character. After the Watergate scandal, they wanted an honest, ethically minded president, and they trusted Carter because he was a born-again Christian.

But some of those evangelicals, especially in suburban areas of the Sun Belt, soured on Carter after they decided he was on the wrong side of the emerging culture wars. Carter was a moderate centrist on abortion and gay rights. He believed strongly in the Equal Rights Amendment and in the historic Baptist value of church-state separation. In his view, he could best apply his Christian values in politics by being honest and ethical and by promoting human rights — not by wading into the culture war controversies of the time.

In this July 31, 1979, file photo, President Jimmy Carter waves from the roof of his car along the parade route through Bardstown, Kentucky. (AP Photo/Bob Daugherty, FIle)

Carter became increasingly estranged from many white evangelicals after they largely deserted his candidacy in 1980. After conservatives acquired control of the Southern Baptist Convention, he followed the more liberal-minded moderates out of the convention and joined the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, which ordained women and eschewed the conservative culture war stances of the SBC.

He continued to teach Sunday school and he prayed more than ever, he said, but he also began writing directly against fundamentalism. By the end of his life, it was clear that his social justice-oriented Christian faith was more akin to ecumenical Protestantism than to conservative evangelicalism in its understanding of Jesus’ message and its relationship to modernity and pluralism. He devoted most of his post-presidency to poverty relief and the promotion of democracy and human rights (including the rights of women and non-Christians) — causes that tended to appeal more to progressive Christians than to most white conservative evangelicals.

By the turn of the century, it was clear that his attempt to combine an experientially based, deeply held evangelical faith with the social justice views of more progressive Christians had not gained much traction among the majority of white evangelicals — even if it did earn the respect of many Christians from a wide variety of theological traditions.

But regardless of how unpopular some of his views might be or how dim the prospects might appear to be for the type of social justice that Carter favored, he had faith that justice and the power of love would ultimately triumph.

“As a Christian, I believe that the ultimate fate of mankind will be good,” he wrote in 2018. “I believe that the love of God will prevail.”

(Daniel K. Williams is professor of history at the University of West Georgia. He is the author of “The Election of the Evangelical: Jimmy Carter, Gerald Ford, and the Presidential Contest of 1976.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

You Might Also Like

New book calls for authentic engagement and equity in organizations

The Nine Asks by Kimberly Danielle Organizations have a responsibility to ensure that people who come there to work, worship,...

‘Holy Hurt’ is Hillary McBride’s field guide to the shattering impact of spiritual trauma

(RNS) — Trauma is a lot like having a shard of glass in your hand, explains clinical psychologist Hillary McBride....

So You Married a Priest? + Beth Allison Barr

It’s ministry by marriage. Did you know there are piles of guidebooks meant to help women excel at...

Abyssinian Baptist Church welcomes dismissal of pastor candidate’s discrimination suit

(RNS) — A federal judge has dismissed a gender discrimination lawsuit brought against Abyssinian Baptist Church by a onetime candidate...