Willice Obonyo (seated) shows his students at the Technical University of Kenya how to use a tabletop radio telescope to observe radio emissions. Credit: Willice Obonyo

Radioastronomy in Africa

In 2005, when South Africa and its partner countries in Africa submitted a proposal to host the world’s largest radio telescope, called the Square Kilometre Array, the continent had five radioastronomers, all based in South Africa. That year, the country embarked on a targeted human-capital development programme to develop talent to build, operate and use radio telescopes, which collect radio signals emitted by celestial objects. Marking its 20th anniversary this year, the government-funded programme has created 5 research-chair positions and more than 1,370 scholarships for undergraduate, master’s, doctoral and postdoctoral studies — at a total cost of about 500 million rand (US$28 million).

Now, the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) is under construction. It will have more than 100,000 tree-like antennas in Australia and almost 200 dish antennas in South Africa. South Africa now owns and operates several radio telescopes, and there are hundreds of radioastronomers and students at universities and institutions in African countries.

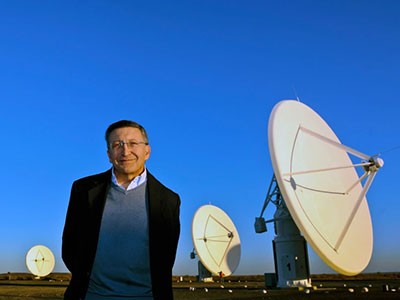

Nature’s careers team spoke to officials and scientists working to grow Africa’s radioastronomy capacity, in part through the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory. In the second of a short series of articles investigating the growth of the discipline on the continent, Willice Obonyo, a lecturer in astronomy and space sciences at the Technical University of Kenya in Nairobi, talks about the importance of hands-on training.

I had always loved space. At school, at about age 12, we were told about constellations and stars, but I didn’t know someone could pursue it as a career. Even when I went to university, there was no option to study astronomy, let alone radioastronomy, which uses radio waves to observe parts of the Universe that are invisible to the naked eye. I ended up earning a bachelor’s of science degree in 2006, and then becoming a mathematics and physics teacher at a secondary school.

In 2011, I went back to Moi University in Eldoret, Kenya, for a master’s in theoretical nuclear physics, and when I was finishing up, a friend told me about the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory (SARAO) scholarships to study astronomy. I asked him about it, then googled ‘astronomy’, and I realized that this was an opportunity to study the Universe. I applied and was accepted into an astrophysics and space science master’s programme at the University of Cape Town (UCT) in South Africa.

Developing astronomers in Africa: ‘We wanted to create a discipline’

The SARAO scholarship gave me an enormous opportunity. It was the first time that I used a telescope: a 1.9-metre optical telescope. In fact, it was the first scientific equipment that I had used hands-on. My education had mostly been theoretical to that point. At the UCT, I could test theories, observe celestial objects for the first time and then process and analyse the data. It was inspiring and it gave me an opportunity to be confident in science and feel that I could be trusted with data for research and interact with leading researchers.

I met and was taught by world-class scholars from various continents. It was a steep learning curve, but there was a lot of help from colleagues and other students. I also received a lot of support from my supervisor Vanessa McBride, who is now the science director at the International Science Council in Paris, an organization that brings global science councils, unions and academies together.

Then, in 2015, South Africa and the United Kingdom were piloting the Development in Africa with Radio Astronomy (DARA) project in African countries, which offered eight weeks of training in basic radioastronomy. It trained me and the other students in the science and technical engineering aspects of radioastronomy, as well as the processing of data. DARA allowed me to transition from optical astronomy into radioastronomy. In 2020, I earned my PhD in physics and astronomy, looking at radio emissions from massive protostars, at the University of Leeds, UK, before returning to Kenya.

You Might Also Like

The Nature Podcast highlights of 2025

You have full access to this article via your institution. Download the Nature Podcast 24 December 2025In this episode:00:40 What...

Seeding opportunities for Black atmospheric scientists

Vernon Morris (outlined) with alumni from the atmospheric sciences PhD programme he established at Howard University in Washington DC.Credit: Vernon...

peer reviews created using AI can avoid detection

The difficulty of detecting AI-tool use in peer review is proving problematic.Credit: BrianAJackson/iStock via GettyIt’s almost impossible to know whether...

I’ve earned my PhD — what now?

Illustration: David ParkinsThe problemDear Nature,In December 2024, I finished my PhD in biomedical chemistry in Italy, and I now find...