Max T. at Maximum Progress shows that between 1992 and 2003 US literacy rates fell dramatically within every single educational category but the aggregate literacy rate didn’t budge. A great example of Simpson’s Paradox! The easiest way to see how this is possible is just to imagine that no one’s literacy level changes but everyone moves up an educational category. The result is zero increase in literacy but falling literacy rates in each category.

Max T. at Maximum Progress shows that between 1992 and 2003 US literacy rates fell dramatically within every single educational category but the aggregate literacy rate didn’t budge. A great example of Simpson’s Paradox! The easiest way to see how this is possible is just to imagine that no one’s literacy level changes but everyone moves up an educational category. The result is zero increase in literacy but falling literacy rates in each category.

Two interesting things follow. First, this is very suggestive of credentialing and the signaling theory of education. Second, and more originally, Max suggests that total factor productivity is likely to have been mismeasured. Total factor productivity tells us how much more output can we get from the same inputs. If inputs increase, we expect output to increase so to measure TFP we must subtract any increase in output due to greater inputs. It’s common practice, however, to use educational attainment as a (partial) measure of skill or labor quality. If educational attainment is just rising credentialism, however, then this overestimates the increase in output due to labor skill and underestimates the gain to TFP.

This does not imply that we are richer than we actually are–output is what it is–but it does imply that if we want to know why we haven’t grown richer as quickly as we did in the past we should direct less attention to ideas and TFP and more attention to the failure to truly increase human capital.

The post Literacy Rates and Simpson’s Paradox appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

You Might Also Like

That Was Then/This is Now

Hat tip: Logan Dobson. The post That Was Then/This is Now appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION. Source link...

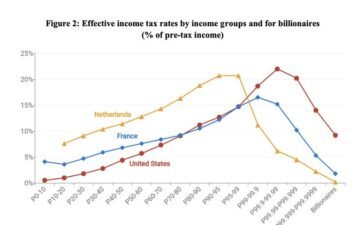

Effective tax rates for billionaires

Here is the tweet, here is the source data. The post Effective tax rates for billionaires appeared first on Marginal...

*You Have No Right to Your Culture: Essays on the Human Condition*

By Bryan Caplan, now on sale. From Bryan’s Substack: My latest book of essays, You Have No Right to Your Culture:...

History of Econ Summer Camp

Graduate students with an interest in the history of economic thought should consider this summer program. Source link...